A potted history of Dowry Square is set out below. If you’re interested in Dowry Square and would be interested in future Dowry Square History Tours, please use the Contact Us page to register your interest. The tours include a visit to the Pneumatic Institution, where Thomas Beddoes and Humphry Davy had their adventures with nitrous oxide!

1700s – Dowry Square provides accommodation for the Clifton Hotwell in its heyday

At the start of the 18th century, following the completion of the Pump Room at Hotwell House, on what is now the Portway beneath the Avon Gorge Hotel, the Hotwell spa was a fashionable destination for high society to take its healing waters. However, the Hotwell itself had limited accommodation, and the surrounding area was rocky and precipitous, so initially most lodging houses were around what is now College Green. As the demand for accommodation increased, and with Clifton at this stage largely unbuilt, Dowry Square was identified as a logical, and importantly, closer site for the construction of boarding houses to serve the spa. It was designed by ‘house carpenter and surveyor’ George Tully in the 1720s, with the houses in the north west corner of the square the first to be completed.

Four of the 16 properties in Dowry Square were clearly designed as larger boarding houses, and these are now flats, but presumably few, if any of them, were single family houses originally.

As described by Vincent Waite in ‘The Bristol Hotwell’, The fashionable procedure for “taking the waters” was to ride in a carriage to the Pump Room in the morning, drink the prescribed number of glasses, and then sit with the company, talking scandal, playing cards, and listening to the small orchestra which exacted a season’s subscription of five shillings from each visitor.

One of the plaques in the square is to William Pennington, who was appointed Master of Ceremonies at the Hotwell towards the end of the 18th century. He published some ‘Rules of the Hotwell’ to ensure that all behaved with decorum at evening events, including the instructions that “a certain row of seats be set apart at the upper end of the room for ladies of precedence and foreigners of fashion. That no gentleman appear with a sword or with spurs in these rooms, or on a ball night, in boots. That on all occasions ladies are admitted to these rooms in hats.”

1800s – demise of the Hotwell spa, experiments with N2O & Bristol’s industrial expansion

Towards the end of the 18th century, the Hotwell spa no longer drew the clientele it once had, and after the Napoleonic wars ended in 1815, the revival of the European Grand Tour further damaged its reputation. The spa continued during the 19th century but it was no longer a major part of Bristol’s historical narrative.

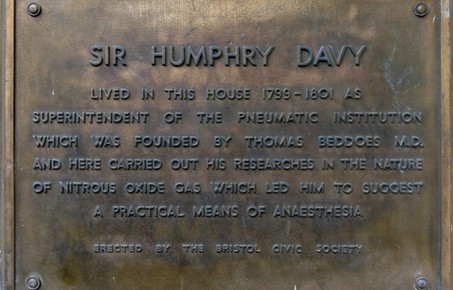

The next significant Dowry Square chapter was in 1799, when Dr Thomas Beddoes, having initially run a clinic in nearby Hope Square, founded the Pneumatic Institution in order to explore the therapeutic use of gases in treating disease. Its superintendent was the young Humphry Davy, whose experiments with nitrous oxide not only hinted at its anaesthetic potential, but also raised profound questions about consciousness that continue to resonate in academic circles today. The after-hours gatherings at the Institution – where illustrious minds such as Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Peter Roget, James Watt, and Robert Southey imbibed the gas and exchanged philosophical musings – became legendary in intellectual circles.

The turn of the 18th century also saw the Cliftonwood hill transformed with the building of Clifton’s premier terraces: Royal York Crescent & Cornwallis Crescent in the 1790s (although the builder of the later became bankrupt so it wasn’t completed until the 1820s), The Paragon in the 1810s and The Polygon in the 1820s. Helen Dunmore’s historical novel Birdcage Walk covers this period well. But unlike the Dowry Square properties, these were houses for the merchant classes, not visitors to the Hotwell.

The 19th century brought complete change to the area. The growth of Bristol’s port infrastructure, and in particular the completion of the floating harbour in 1809, meant that much of Hotwells & Spike Island were taken over by port infrastructure, its ancillary industries and workers. As part of forming the floating harbour, the New Cut river was dug out over five years – an incredible achievement if you’ve ever stood on Gaol Ferry Bridge and looked down.

In the square, the Clifton Dispensary was founded in 1812 by Thomas Whippie, which provided accessible medical care to the under-served local population as an alternative to hospitals and private doctors. The idea was to carry on the spirit of Thomas Beddoes’ work, providing proper medical care for people who couldn’t afford to see a private doctor. It also contributed to medical education, providing practical training and hands-on experience for students of the Bristol Medical School. The Dispensary kept going right up until the founding of its spiritual successor – the NHS – in 1948, which finally made free healthcare available to everyone.

Also in 1812, Jacob Schweppe, a Swiss entrepreneur, established a shop offering carbonated mineral water sourced directly from the Hotwells spa, thus laying the foundation for one of the world’s most recognisable beverage brands.

At this time, before the development of the modern road system, the area from Dowry Square down to the docks was full of hotels, pubs, shops and the general busyness of the times.

1900s – business use, post war changes & conservation

A hand drawn map from the 1920s shows the area full of businesses. York Hotel in one corner of the square across from Dowry Hotel. The former stables in the north west corner of the square was Colman’s builders merchants for the whole of the century. Around this time The Hotwells Nursery and School for Mothers was also formed in the square.

During World War II, the garden was repurposed for livestock by a local butcher and we have photos of sheep grazing in the then fully-grassed and treeless square. Fortunately, unlike much of central Bristol, Dowry Square survived the blitz, although Trinity Church on Hotwell Road was hit.

A big change to the local area came in the 1960s when the Cumberland Basin road system was constructed that bridged the floating harbour and New Cut to connect traffic to the portway and the town centre. Thereafter, Hotwells Road, which runs along the southern side of Dowry Square became one of the key arterial routes into the city, hence Dowry Square has had a three lane road on its boundary ever since. As part of the scheme, the local river frontage was completely altered, with whole streets demolished. At the same time St Andrew-the-Less church in Dowry Parade, was also demolished, to be replaced by Carrick House – a block of 20 flats.

By this time the lower Cliftonwood area was very dilapidated, with low house prices and to an extent the same was true of Clifton. Many of the Dowry Square properties at this stage were occupied by businesses, and there were development threats to the whole area. Dowry Square owes a huge debt to the dedication of architect Peter Ware (1929–1999), a former resident of the square, who was instrumental in preserving its historic charm against the encroaching tide of often unsympathetic city planning. Today, a plaque on the South side of the railings stands in tribute to his commitment.

2000s – renewal and community spirit

Over the last 30 years the sense of local community spirit has burgeoned. Following the conversion of Colman’s yard into two modern (well insulated) properties, and the departure of the businesses, the square is now almost completely residential. The garden is well-loved and tended by the residents, including mature trees, herbaceous borders, a pond, bird boxes, a raised bed for vegetables and, most recently, a children’s play area with mud kitchen!

Whilst there is no threat to Dowry Square itself, the Western Harbour plans could have a significant local impact if the scheme goes ahead to its fullest extent.